Route 66: The Long Road Out of Depression Into a Century of Optimism

Established in 1926, the ensuing Great Depression meant the story of Route 66 became a road from and to despair for some, and a quirky, nostalgic trip for others, depending on era and circumstance.

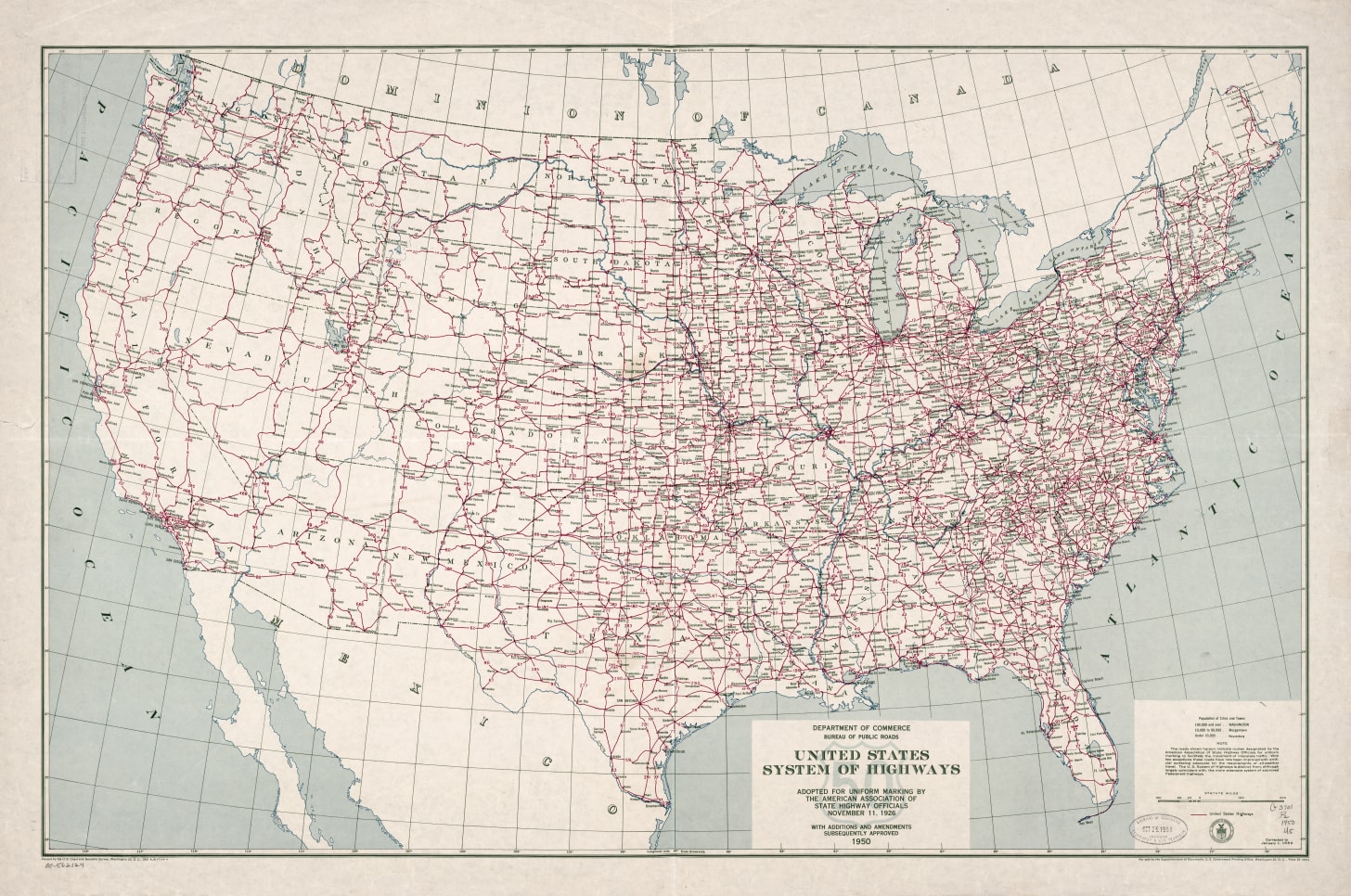

Route 66, established in 1926, played a crucial role in American history, particularly during the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl era of the 1930s. It served as a critical artery for migration, economic survival, and cultural transformation. Herein, we briefly examine the practical and cultural significance of Route 66 during its early period, focusing on its role in facilitating migration, economic shifts, and its enduring cultural legacy.

During the 1930s, Route 66 emerged as one of the most significant highways in American history, both practically and culturally. Although it wasn’t completely paved until 1938, as the country faced the devastating effects of the Great Depression and the environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl, tens of thousands of displaced families1 turned to this road as a path toward hope and opportunity.

Route 66 became a crucial migration route, offering a means of escape for those fleeing economic despair and environmental ruin, particularly farmers from Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, and other affected regions. Often known as “Okies” — that Okie epithet was almost always a disparaging pejorative — the influx of migrants into California led to tensions, as the state struggled to accommodate the new arrivals. At the California border, officials attempted to turn back migrants, citing overcrowded relief rolls and limited job opportunities. Despite these challenges, Route 66 remained a symbol of hope and a pathway to potential prosperity for those escaping environmental and economic hardships.

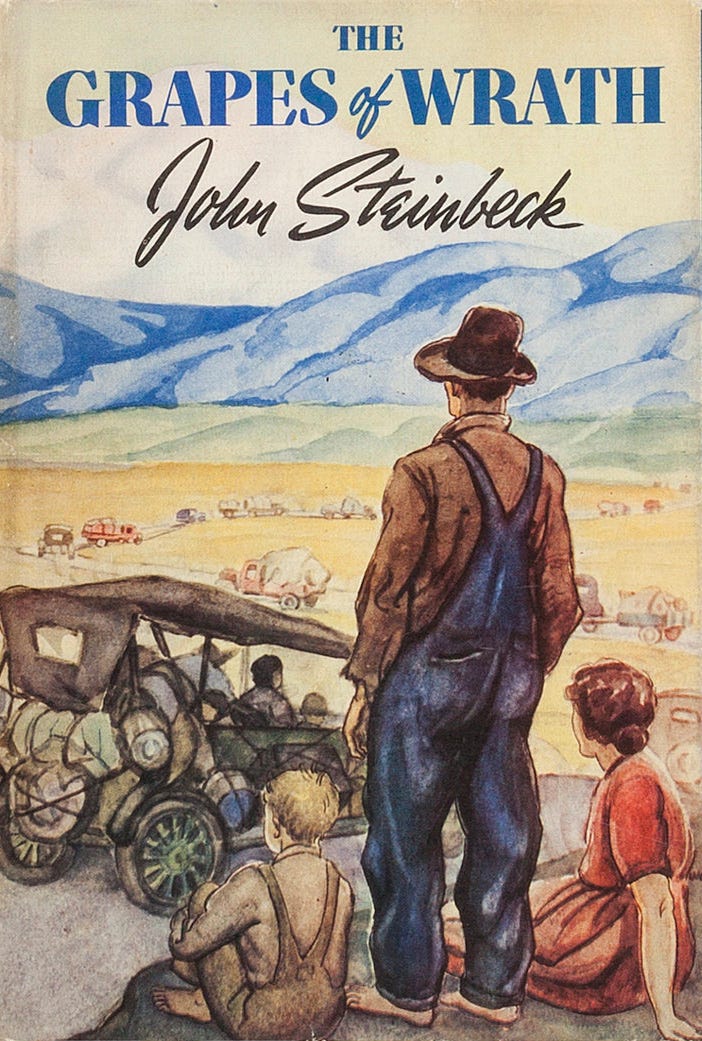

The road, immortalized in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, symbolized both the hardships and the resilience of the American people during this tumultuous period.

Practically, Route 66 served as a critical artery for migration, enabling thousands of Dust Bowl refugees to travel westward toward California. The promise of agricultural jobs and a fresh start in the fertile valleys of California encouraged these desperate families to undertake the arduous journey. With limited resources, many piled their belongings onto overloaded vehicles and traveled the "Mother Road," seeking better conditions. Gas stations, auto repair shops, and diners along the route adapted to accommodate these weary travelers, marking the beginning of Route 66’s economic significance.

Culturally, Route 66 became deeply ingrained in the American consciousness as a road of struggle, resilience, and reinvention. Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath vividly depicted the plight of migrating families, cementing Route 66 as a symbol of hardship and hope. The highway’s influence extended beyond literature, shaping folk music, photography, and oral histories that documented the migrant experience. The roadside businesses that flourished along the route laid the foundation for a uniquely American car culture, fostering the development of motels, roadside diners, and service stations that would later become iconic.

Despite the challenges faced by migrants, Route 66 embodied the spirit of determination that defined an era. It was more than just a road; it was a passage toward survival, a corridor of cultural exchange, and a testament to the resilience of the American people. Even today, Route 66 remains a powerful symbol of American identity, its legacy deeply rooted in the struggles and triumphs of those who traveled its path during the Great Depression.

John Steinbeck’s Literary Portrait of the Era: The Grapes of Wrath

Synopsis: The Grapes of Wrath (1939) chronicles the journey of the Joad family, a group of tenant farmers forced to leave their Oklahoma home during the Dust Bowl. Like tens of thousands of other families, they set out on Route 66, heading toward California in search of work and a better life. The novel portrays their struggles, hardships, and encounters with both cruelty and kindness along the way, ultimately serving as a stark critique of economic injustice and social inequality in America.

The Joads, led by the determined yet struggling Tom Joad and the resilient Ma Joad, leave their dust-ravaged farm after being evicted by landowners and banks. Armed with little more than hope, they pack their meager possessions onto a battered truck and embark on a treacherous journey westward. Along Route 66, they meet fellow migrants who share their dreams but also their despair, as stories circulate about the harsh realities awaiting them in California.

When they arrive, the Joads quickly discover that the promised land is far from paradise. Jobs are scarce, wages are exploitative, and migrant workers are treated with suspicion and hostility. They experience firsthand the brutal cycle of poverty and oppression as they move from one labor camp to another, facing hunger, violence, and the constant threat of being driven out. Tom Joad, initially optimistic, becomes increasingly radicalized after witnessing injustices against workers. He is ultimately forced to flee after killing a man in self-defense, leaving his mother and family to continue the fight for survival.

The novel’s final scene, one of the most haunting in American literature, encapsulates Steinbeck’s themes of resilience, human dignity, and shared suffering. After the Joads take refuge in a barn during a flood, they encounter a starving man. Rose of Sharon, Tom’s sister, who has just lost her newborn baby, offers him her breast milk to keep him alive. Offering breast milk to a starving man demonstrates the ability to give life and support even in the face of unimaginable loss, and thus Rose of Sharon becomes a symbolic act of compassion and communal survival amidst hardship and deprivation.

Steinbeck’s novel wrestles with —

The Struggles of Migrant Workers: The novel paints a harsh picture of the economic system that exploits desperate laborers, showing how big landowners and corporations pit workers against each other to drive down wages. The Joads, like many real-life migrants, endure brutal conditions in their pursuit of honest work.

The Power of Family and Community: Despite their suffering, the Joads rely on each other for strength. Ma Joad, in particular, becomes the novel’s moral center, emphasizing endurance and solidarity. The novel suggests that only through collective action and mutual support can people survive and resist oppression.

The Corrupting Influence of Wealth and Power: Steinbeck condemns the greed of banks and large landowners, portraying them as faceless forces that destroy lives in pursuit of profit. The Joads’ eviction from their land and their subsequent exploitation in California highlight the brutal realities of economic inequality.

Man vs. Nature: The Dust Bowl serves as both a literal and symbolic force in the novel. It represents the environmental devastation that displaces the Joads and thousands of others, but it also symbolizes the unrelenting hardships they face.

The Road as a Symbol of Hope and Despair: Route 66, the path westward, is depicted as both an escape and a cruel illusion. It promises a new beginning, but for many migrants, it leads only to further suffering and disenfranchisement.

The Grapes of Wrath remains one of the most influential novels of the 20th century, providing a deeply moving and historically accurate portrayal of the Dust Bowl migration. It continues to serve as a poignant reminder of economic struggle, human endurance, and the pursuit of justice. It reflects both the solidarity and the struggles of migrant families along Route 66, illustrating the highway’s dual nature as a road of both hope and disillusionment.

This era saw the largest internal migration in U.S. history, with approximately 2.5 million people leaving the Plains states by 1940, and at least 200,000 of them moving to California.