Artificial Intelligence and the Destiny of Human Language

The vital role of the bold voice of faith in the big tech / AI conversation

Veritas Chronicles Editorial: We are by no means unbiased observers of the “big tech / artificial intelligence” conversation. In fact, we reject the notion that there are any unbiased parties to this, or any conversation, happening anywhere on the globe. With that context, we ask these questions (not all can be answered in this article or in any one discussion because they are of ongoing import): Are humans destined to become merely a subset of the language of computer science in the form of artificial intelligence and machine learning? If, in the beginning there was the Word, is there any reason to think that human language and destiny will descend to the realm of 1’s and O’s? Is it possible for machines to obtain a certain kind of free will that might supersede the free will thinking capacity of humans? Is it possible that the enticings of good and evil are to be joined by a third and completely independent voice to which human beings might become subject? Or is there a superior language that already shapes human destiny, where free will is the gift that will never be superseded by a mere product of earth, no matter how advanced? What is the role of faith (and works) in the current and future AI conversation? Veritas Chronicles has positioned itself to be an active observer of the big tech / AI conversation from the perspective of faith in the Divine Destiny of Creation. In this article we note one voice of faith in particular, that of Father Philip Larrey as an example of a qualified Christian faith voice in the global artificial intelligence dialogue. (To read the complete story download the attached pdf file.)

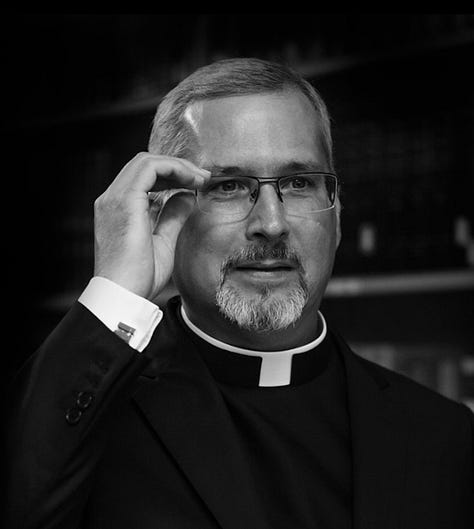

Father Philip Larrey was Chair of Logic and Epistemology at the Pontifical Lateran University in the Vatican, and was the Dean of the Philosophy Department; presently Professor of Philosophy at Boston College. Fr. Philip is one of the visible / audible voices of faith in the global artificial intelligence dialogue.

NATIONALISM IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE — as reported in the New York Times, Wednesday August 14, 2024

By Adam Satariano and Paul Mozur

As artificial intelligence advances, many nations are worried about being left behind.

The urgency is understandable. A.I. is improving quickly. It could soon reshape the global economy, automate jobs, turbocharge scientific research and even change how wars are waged. World leaders want companies in their country to control A.I. — and they want to benefit from its power. They fear that if they do not build powerful A.I. at home, they will be left dependent on a foreign country’s creations.

So A.I. nationalism — the idea that a country must develop its own tech to serve its own interests — is spreading. Countries have enacted new laws and regulations. They’ve formed new alliances. The United States, perhaps the best positioned in the global A.I. race, is using trade policy to cut off China from key microchips. In France, the president has heaped praise upon a startup focused on chatbots and other tools that excel in French and other non-English languages. And in Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is pouring billions into A.I. development and striking deals with companies like Amazon, I.B.M. and Microsoft to make his country a major new hub.

“We must rise to the challenge of A.I., or risk losing the control of our future,” warned a recent report by the French government.

In today’s newsletter, we’ll explain who is winning and what could come next.

ChatGPT’s impact

The race to control A.I. started, in part, with a board game. In 2016, computers made by Google’s DeepMind won high-profile matches in the board game Go, demonstrating a breakthrough in the ability of A.I. to behave in humanlike ways. Beijing took note. Chinese officials set aside billions and crafted a policy to become a world leader in A.I. Officials integrated A.I. into the country’s vast surveillance system, giving the technology a uniquely authoritarian bent.

A high-school ChatGPT workshop in Walla Walla, Wash. Ricardo Nagaoka for The New York Times

Still, China’s best firms were caught off guard by OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT in 2022. The companies raced to catch up. They’ve made some progress, but censorship and regulations have hampered development.

ChatGPT also inspired more countries to join the race. Companies in the United Arab Emirates, India and France have raised billions of dollars from investors, with varying degrees of state aid. Governments in different nations have provided subsidies, bankrolled semiconductor plants and erected new trade barriers.

America’s advantage

The U.S. has advantages other countries cannot yet match. American tech giants control the most powerful A.I. models and spend more than companies abroad to build them. Top engineers and developers still aspire to a career in Silicon Valley. Few regulations stand in the way of development. American firms have the easiest access to precious A.I. chips, mostly designed by Nvidia in California.

The White House is using these chips to undercut Chinese competition. In 2022, the U.S. imposed new rules that cut China off from the chips. Without them, companies simply cannot keep pace.

The U.S. is also using chips as leverage over other countries. In April, Microsoft worked with the U.S. government to cut a deal with a state-linked Emirati company to give it access to powerful chips. In exchange, the firm had to stop using much of its Chinese technology and submit to U.S. government and Microsoft oversight. Saudi Arabia could make a similar deal soon.

What comes next

Looming over the development of A.I. are lessons of the past. Many countries watched major American companies — Facebook, Google, Amazon — reshape their societies, not always for the better. They want A.I. to be developed differently. The aim is to capture the benefits of the technology in areas like health care and education without undercutting privacy or spreading misinformation.

The E.U. is leading the push for regulation. Last year, it passed a law to limit the use of A.I. in realms that policymakers considered the riskiest to human rights and safety. The U.S. has required companies to limit the spread of deep fakes. In China, where A.I. has been used to surveil its citizens, the government is censoring what chatbots can say and restricting what kind of data that algorithms can be trained on.

A.I. nationalism is part of a wider fracturing of the internet, where services vary based on local laws and national interests. What’s left is a new kind of tech world where the effects of A.I. in your life may just depend on where you live.