What Gives?

“At least twenty countries that have received billions of dollars’ worth of aid are poorer now.” Can we learn give more sustainably?

by Kristen Star Borchers with Peter R. Rancie

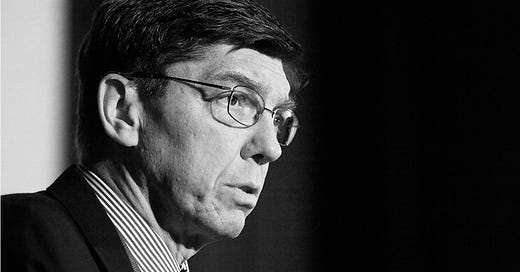

THE PROSPERITY PARADOX by Clayton M. Christensen, Efosa Ojomo, and Karen Dillon focuses on market-creating innovations as the real key for lasting economic development, and as an antidote for various forms of unsustainable giving.

To establish their premise, the authors describe examples of well-intentioned development projects, in numerous countries. Even after the investment of much time, sweat equity, and material resources, the cited projects did not lead to positive and sustainable uplift at the local level, though the resources were intended to deliver positive change.

The book argues that many well-intentioned aid projects in impoverished regions fail to create lasting change because they don’t address the root causes of poverty and economic stagnation. Such projects may deliver resources or infrastructure, but without due consideration of the ability of local communities to maintain them, the communities being served can hardly make the most of these new resources to project and implement methods for prolonged growth for the future. In many cases, these projects could even create dependency, as external organizations are needed to sustain them.

The trigger for the research that inspired this book, was the failure despite very noble intentions, of a water well project in a remote African region. While these wells initially provided access to clean water, they required ongoing maintenance, spare parts, and expert knowledge to keep them functional. As often happens when these elements are not in place, the wells rapidly fell into disrepair, leaving communities worse off than before due to their dependence on a newly acquired resource they could no longer maintain.

Traditional aid and development efforts in impoverished regions are often likened to providing severely parched individuals with small cups of water. Despite good intentions, this approach fails to create lasting positive change and often perpetuates dependency on external assistance.

The admirable motivation of “providing for” less fortunate individuals is a long-standing tradition amongst governments, NGOs, and private givers. However, the unsustainability of many “traditional giving” projects has been witnessed firsthand in challenged areas in the United States, Latin and South America, the Caribbean, Malaysia, Europe, Israel, Egypt, Australia, East Africa, and truly all around the globe by the co-founders of Veritas Chronicles. That is not to say giving is not good. It is. Exceedingly. Giving is necessary for the spiritual and emotional growth and good of the giver and the receiver and easily crosses all cultural, ethnic, religious and racial boundaries.

Giving can and should be viewed as a positive and virtuous act that produces and enriches altruism, empathy and compassion, creates positive social bonds, brings a sense of fulfillment, reduces inequality, and provides a way for humanity to live out values and beliefs or engage in traditional customs and cultural traditions.

Giving promotes gratitude for what we already have, what we can share, and for that which has been newly provided. Our observation is that feelings of wellbeing increase with giving and incite a belief in reciprocity where a cycle of mutual support and goodwill are created. Giving is a critical contribution to a better society.

When individuals and communities engage in giving, it can contribute to the creation of a more compassionate and caring global community. It’s important to note that giving doesn’t always have to involve material goods or financial donations. It can also include giving time, skills, knowledge, or emotional support. Ultimately, the act of giving is considered good because it embodies the foundational principle of helping others and contributing to the well-being of the broader community, which is a fundamental aspect of human cooperation and social progress. We observe that societies where giving is prevalent, are better places to live.

All examples of giving are good, but best when they have enduring impact. Some forms of giving, such as investing in education or healthcare, can have long-term positive effects on individuals and communities, breaking cycles of poverty and leading to more prosperous futures.

Long-lasting sustainable impact, around the globe, for the betterment of society, by those who are creating good and maintaining it for sustainable enrichment, is what Christensen was proposing to celebrate and promote, and where Veritas Chronicles is focused on shining its publishing light.

Without diminishing the value and absolute necessity of “traditional aid” i.e. giving out cups of water to the thirsty, the authors of The Prosperity Paradox introduce the idea of “market-creating innovations” as metaphorical water producing wells. These wells represent investments in local businesses and industries that have the potential to catalyze economic growth from within. They focus on creating self-sustaining systems that provide not just immediate relief, but long-term prosperity for communities. This approach moves beyond short-term aid to foster entrepreneurship, economic empowerment, and the development of sustainable societal transformation. But how do we get there?

The digging of wells is a real example, but it also serves as a metaphor to illustrate the central thesis of the book: real prosperity can only be achieved when we enable and empower local entrepreneurs and businesses to grow and thrive.

When local people and businesses can generate their own prosperity, they are more likely to maintain and expand these opportunities, creating a virtuous and sustainable cycle of development. The authors cite numerous real-world examples to emphasize this point. One of the most prominent stories highlighted is that of Safaricom and M-PESA in Kenya.

Christensen relays that Safaricom’s introduction of M-PESA, a mobile money transfer service, was transformative for the nation. “More than 85 percent of Kenyans did not have access to banking services before M-PESA”. It took the Kenyan banking system over one hundred years to create its estimated 1,200 bank branches, but M-PESA, since its release in 2007, has engaged more than twenty-two million Kenyans and its service contracts upwards of $4.5 billion monthly. There are now more than forty thousand M-PESA agents in the country, gaining valuable income from the opportunity to work. Not only has M-PESA brought transformational banking to a nation, the preponderance of which was entirely unbanked, but the entrepreneurial company has also afforded the population access to other financial service products in the form of loans and insurance that were up till the release of M-PESA, unavailable to the bulk of the nation.

It not only revolutionized the way people conducted financial transactions but also created a thriving ecosystem of entrepreneurs and businesses that leveraged this innovation. M-PESA became a wellspring of economic opportunities for Kenyans, empowering individuals to start their own businesses and improve their livelihoods. Betterment of livelihoods generally translates to betterment of living conditions, increased family provisions, increased education opportunities and access to better healthcare, among others.

The book’s authors stress that the success of M-PESA and similar innovations lies in the ability to address fundamental needs of the local population and create a self-sustaining ecosystem. This transformation, driven by market-creating innovations, can lead to a domino effect, opening up opportunities in various sectors and benefiting a wide range of people.

The relationship between these metaphorical wells and sustainable societal transformation is profound. The wells, representing market-creating innovations, are key to breaking the cycle of poverty and dependency. They enable individuals and communities to take control of their economic destiny, fostering self-reliance and entrepreneurship. This shift in mindset and approach is fundamental to creating positive social impact that endures over time.

It also exemplifies how empowering local entrepreneurs and businesses can lead to sustainable societal transformation and positive social impact. By creating opportunities for individuals and communities to thrive, we can collectively work towards a world where poverty is replaced with prosperity, and where long-lasting, positive change becomes normalized. The Prosperity Paradox has an upbeat view of the world in the sense of our ability to collectively problem solve; at Veritas Chronicles, we share that view.

Christensen encourages us to shift our focus from providing short-term aid to supporting initiatives that enable the creation of new markets, self-sufficiency and economic growth within impoverished communities. We must take on a holistic approach that addresses the root causes of poverty, one that empowers local entrepreneurship, to engage in a process that will lead to lasting change. §