What do Mutiny on the Bounty, and Australia's penal colonies, and a Pacific paradise, that was once a hell hole, have in common?

Answer: Norfolk Island | A story of transformation

There is an indirect relationship between the author and the island described herein, much more significant than a memorable week spent collecting the images attached to this article. The first Australian “Rancie” was just 14 years old, caught up in the “sweeping of the streets” - the British government policy designed to depopulate the underclass, clear the jails, and empty the hulks (prison ships) floating in the Thames River. That policy spawned the penal settlements of the South Pacific, specifically Terra Australis, later Australia, commencing in 1788. The unfortunate teenager was transported for a petty crime for seven years (effectively a life sentence) to a larger island, Tasmania, in 1835. There, the governance was almost identical to that of Norfolk Island; the historic relics are very similar; the reputation for being assigned the worst of the transported convicts was similar; so a week long visit to Norfolk Island felt like a piece of family history research.

Nestled in the South Pacific Ocean between Australia, New Zealand, and New Caledonia, Norfolk Island is known today for its serene landscapes, breathtaking coastline, and towering Norfolk pines. Yet, this tranquil facade belies a dark and harrowing past. Norfolk Island’s history as one of the British Empire’s most notorious penal settlements is marked by unimaginable brutality, suffering, and human endurance. Despite its paradisiacal setting and strong tourism interest, the island has ongoing modern struggles, especially with resources. However, it also serves as an excellent example of transition from somewhat depraved beginnings to a modern, flourishing society.

The Early Penal Settlements (1788-1855)

The story of Norfolk Island’s penal history began shortly after the British settled Australia. In 1788, Governor Arthur Phillip dispatched Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to establish a settlement on the island. King arrived with a small party of convicts and soldiers, tasked with utilizing the island's resources and deterring other European powers from colonizing the area. Yet from the beginning, life on Norfolk Island was marked by hardship and scarcity. The early settlers struggled with the island's dense forests, infertile soil, and the remoteness that made resupply difficult. Convicts endured relentless labor, clearing the land and constructing basic infrastructure, all while facing brutal punishments for even minor offenses.

Despite the hardships of the first settlement, it was the second penal colony, reestablished in 1825, that would become infamous. This time, Norfolk Island was reserved for the most hardened and recalcitrant convicts — men who had already committed additional crimes after being transported to Australia. The British government’s intention was clear: Norfolk Island would be a place of unrelenting punishment, a purgatory where convicts suffered with no hope of redemption.

Hell on Earth: The Brutality of the Second Settlement

The harshness of life on Norfolk Island during the second settlement is difficult to overstate. The penal colony was designed to break men both physically and psychologically, and numerous accounts from the time illustrate this hellish existence.

The Chain Gangs

Convicts were forced into chain gangs, where they labored from dawn until dusk in all weather. Given its position in the Pacific, the sun’s rays were usually penetratingly fierce. The chains used to shackle their ankles were heavy and cruel, often causing deep, festering wounds that never fully healed. One convict, John Knatchbull, later testified about the misery of working in these chains, recounting how the constant chafing led to infections so severe that prisoners would beg for their legs to be amputated. Even when convicts fell ill or collapsed from exhaustion, they were expected to continue working or face brutal consequences.

The Whipping Yard

Punishment by flogging was a common occurrence, with the whipping yard serving as a grim theater of pain and humiliation. Floggings were often public, intended to break not just the spirit of the offender but to terrorize the entire convict population. One particularly horrifying account describes a convict named William Westwood, also known as "Jackey Jackey," who was subjected to 100 lashes for a minor infraction. Witnesses reported that his back was flayed open, the flesh hanging in ribbons, and that the pain was so severe he fell unconscious. Yet, the overseers revived him with buckets of salt water, only to continue the punishment. Many men never fully recovered, with some dying from their injuries days or weeks later.

The Torture of Solitary Confinement

Solitary confinement on Norfolk Island was another method of psychological torment. Prisoners were placed in pitch-black cells, devoid of light and sound, for weeks or even months. The cells were damp and rat-infested, and convicts often emerged from confinement hallucinating or driven mad. One account describes a convict named Patrick Feeney, who was confined for weeks and later found muttering incoherently, his mind shattered. Another man, who spent a month in solitary confinement, was discovered clawing at the walls, having scratched his fingernails to the bone in a desperate attempt to escape the darkness.

The Unbearable Work in the Quarries

The limestone quarries were another site of immense suffering. Convicts were forced to quarry and transport heavy stones, with overseers whipping anyone who faltered. The dust from the quarry work caused severe respiratory issues, and convicts often collapsed from exhaustion. One particularly tragic story is that of a young convict named Thomas Lowe, who, after weeks of labor, fell under the weight of a massive stone block he was forced to carry. The overseers showed no mercy, and Lowe's crushed body was left as a warning to others.

The Psychological Torment of Execution

Perhaps one of the most haunting aspects of the penal settlement was the use of executions as a method of instilling fear. One of the most chilling events was the execution of several convicts following the failed 1834 "Cooking Pot Uprising." These men had conspired to overthrow their guards and escape but were betrayed and captured. As punishment, they were hanged in front of the entire convict population. Witnesses described the terror etched on the faces of those about to be executed, and the audible sobbing of convicts who were forced to watch their fellow prisoners die. The gallows became a symbol of ultimate despair, and many convicts reportedly committed minor crimes, hoping to be executed rather than endure the continuing torment of life on Norfolk Island.

Major Joseph Childs and the Reign of Terror

Major Joseph Childs, one of the most notorious commandants, enforced a regime of sheer brutality. His philosophy was simple: punish any deviation from absolute obedience with extreme measures. Under Childs, the penal colony became even more oppressive. Floggings increased, and the punishments became even more arbitrary. There are records of convicts being punished for offenses as trivial as speaking out of turn or failing to complete a task to the overseer's satisfaction. One convict, in his later testimony, described the atmosphere under Childs as a “perpetual state of terror,” where any small misstep could result in severe and often life-threatening punishment.

The Pitcairn Islanders and a New Chapter (1856 Onward)

After the closure of the penal colony in 1855, Norfolk Island was given a new lease on life. In 1856, the descendants of the HMS Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian companions were relocated from Pitcairn Island to Norfolk. These settlers, resilient and industrious, transformed the island from a place of punishment into a vibrant community. They cultivated the land, established farms, and wove their Polynesian and British heritage into the island’s identity.

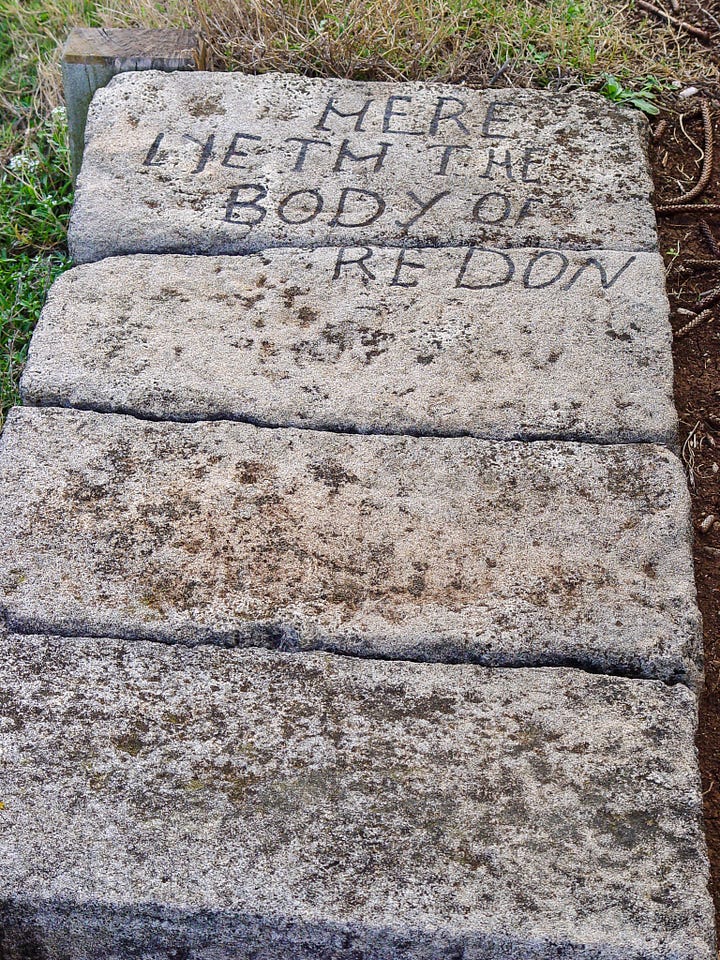

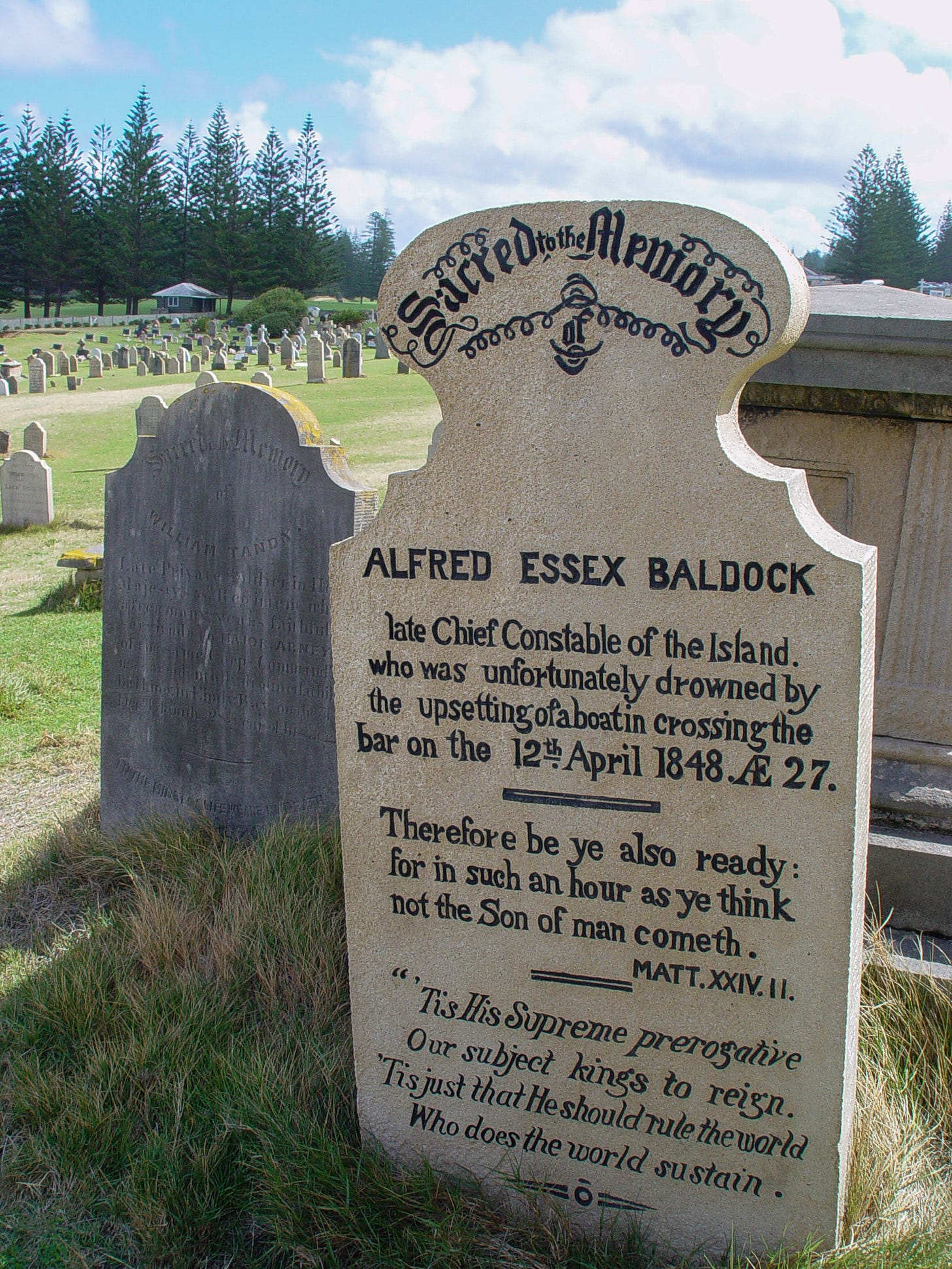

Although the Pitcairn Islanders created a new narrative for Norfolk Island, the ruins of the penal settlements remained, casting long shadows over the landscape. Today, the crumbling buildings are a stark reminder of the island's dark past and draw historians and tourists eager to learn about this chapter in colonial history.

20th Century Developments and Governance Struggles

Throughout the 20th century, Norfolk Island underwent several changes. The island’s strategic importance was evident during World War II when an airstrip was constructed to support the Allied war effort. After the war, Norfolk Island transitioned to a quiet outpost under Australian oversight. In 1979, the island gained self-governance, allowing it to manage many of its internal affairs, though Australia retained control over defense and foreign policy.

The island’s economic reliance on tourism has made it vulnerable to global economic fluctuations and crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2015, citing economic and administrative inefficiencies, Australia revoked Norfolk Island’s self-governing status, sparking protests and a sense of betrayal among the islanders. Many felt their unique identity and cultural heritage were being undermined, and debates over governance continue to this day.

Contemporary Challenges

Norfolk Island’s modern struggles are numerous. Economically, the island faces high costs of living due to its reliance on imported goods. Efforts to diversify the economy through sustainable tourism and agriculture are ongoing but challenging. Environmental conservation is another pressing issue, as the island’s unique ecosystems face threats from invasive species and climate change. Cultural preservation remains a top priority for the islanders. The descendants of the Pitcairn Islanders are determined to maintain their customs, language, and traditions, but balancing modernity with cultural heritage is an ongoing struggle.

Conclusion

Norfolk Island’s history is a testament to human suffering and resilience. The brutal penal settlements left indelible scars on the island, but they also revealed the unbreakable spirit of those who endured unimaginable torment. Today, the island stands at a crossroads, grappling with economic vulnerability, environmental threats, and cultural preservation. Yet, the community’s strength, rooted in a deep understanding of their history, continues to inspire hope for a brighter and more sustainable future. The story of Norfolk Island is one of survival against the odds, a place where history is ever-present, and the struggle for a self-determined future remains ongoing.